Terra Plasma+: Experiments on Shifted Gaze Towards Soil, A Garden for Caring: Curing with Plasma

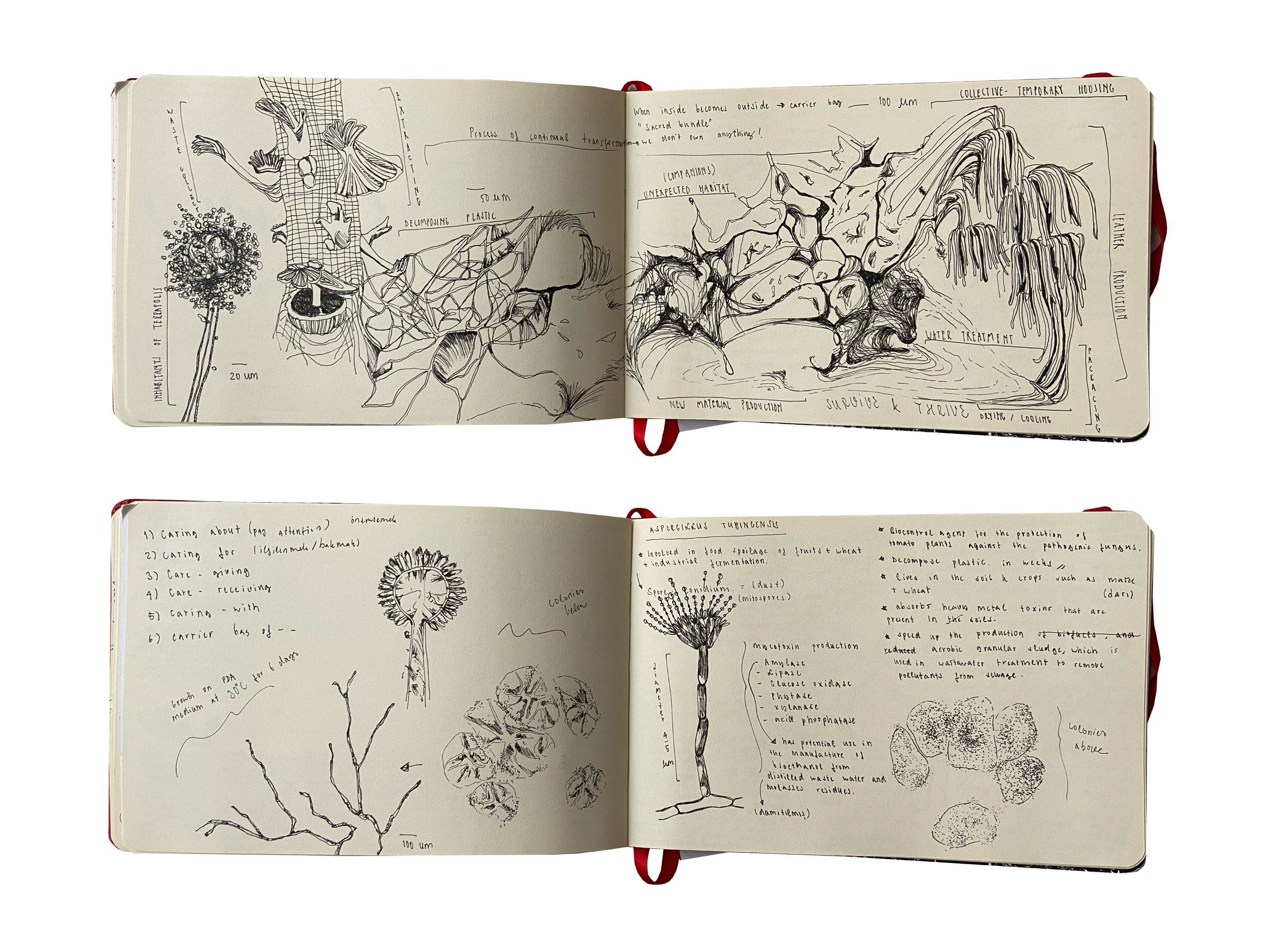

The term “plasma” originally meant “form, shape” (a now obsolete sense), derived from the Greek “plasma,” meaning something molded or created. From Late Latin “plasma,” the term evolved into a mid-17th-century usage referring to molding, with origins from the Greek word “plastikos,” meaning “to mold.”

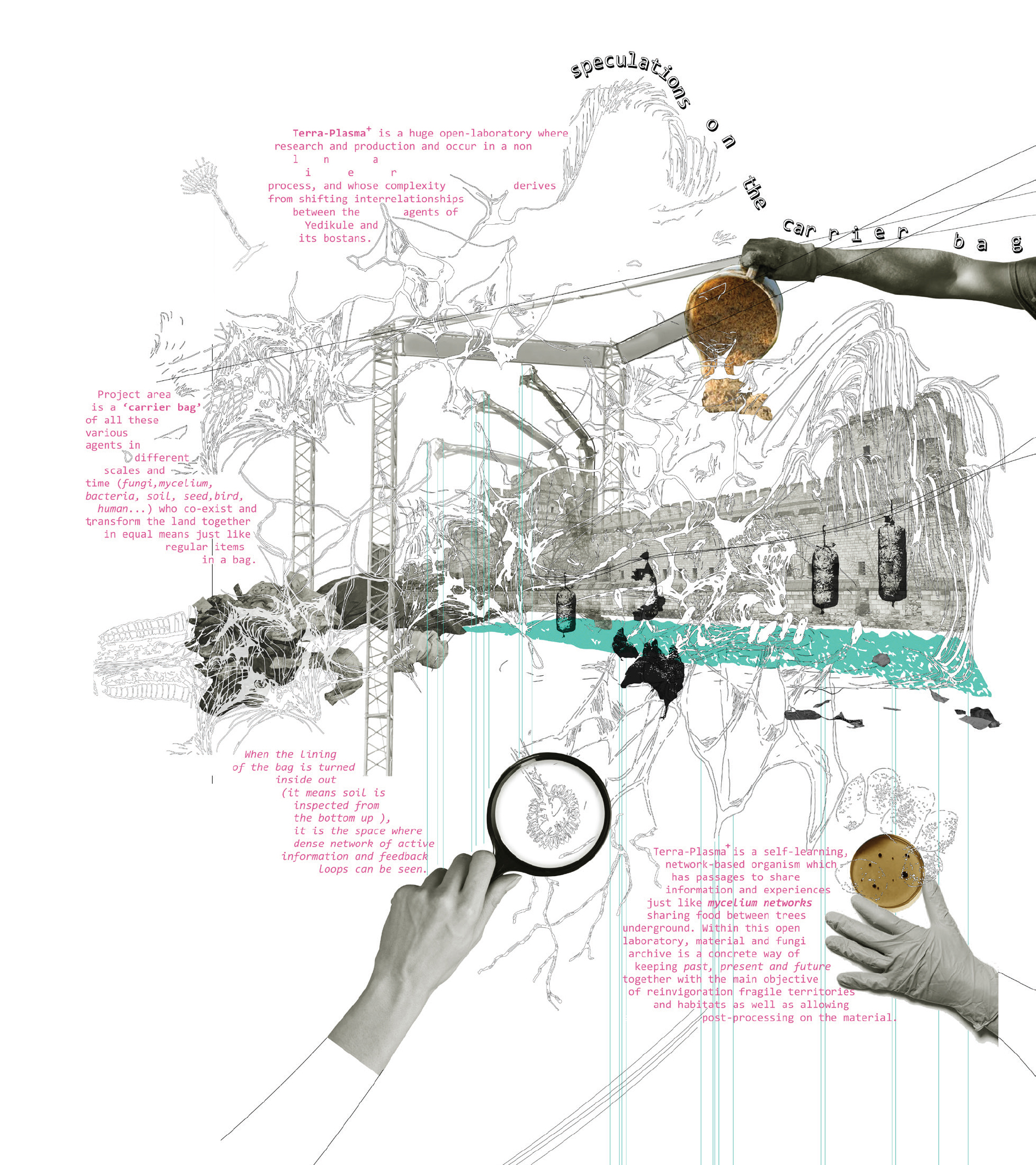

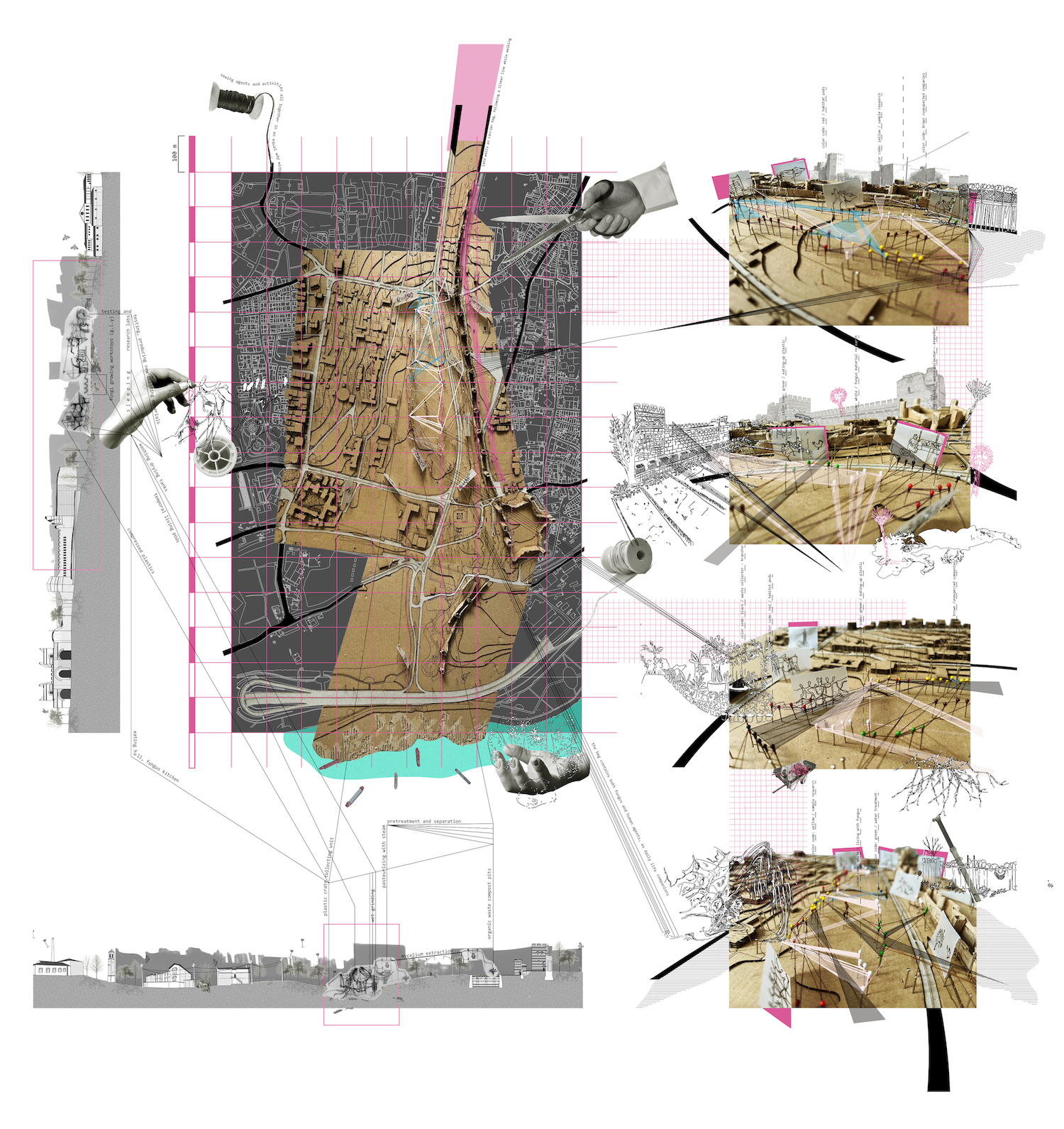

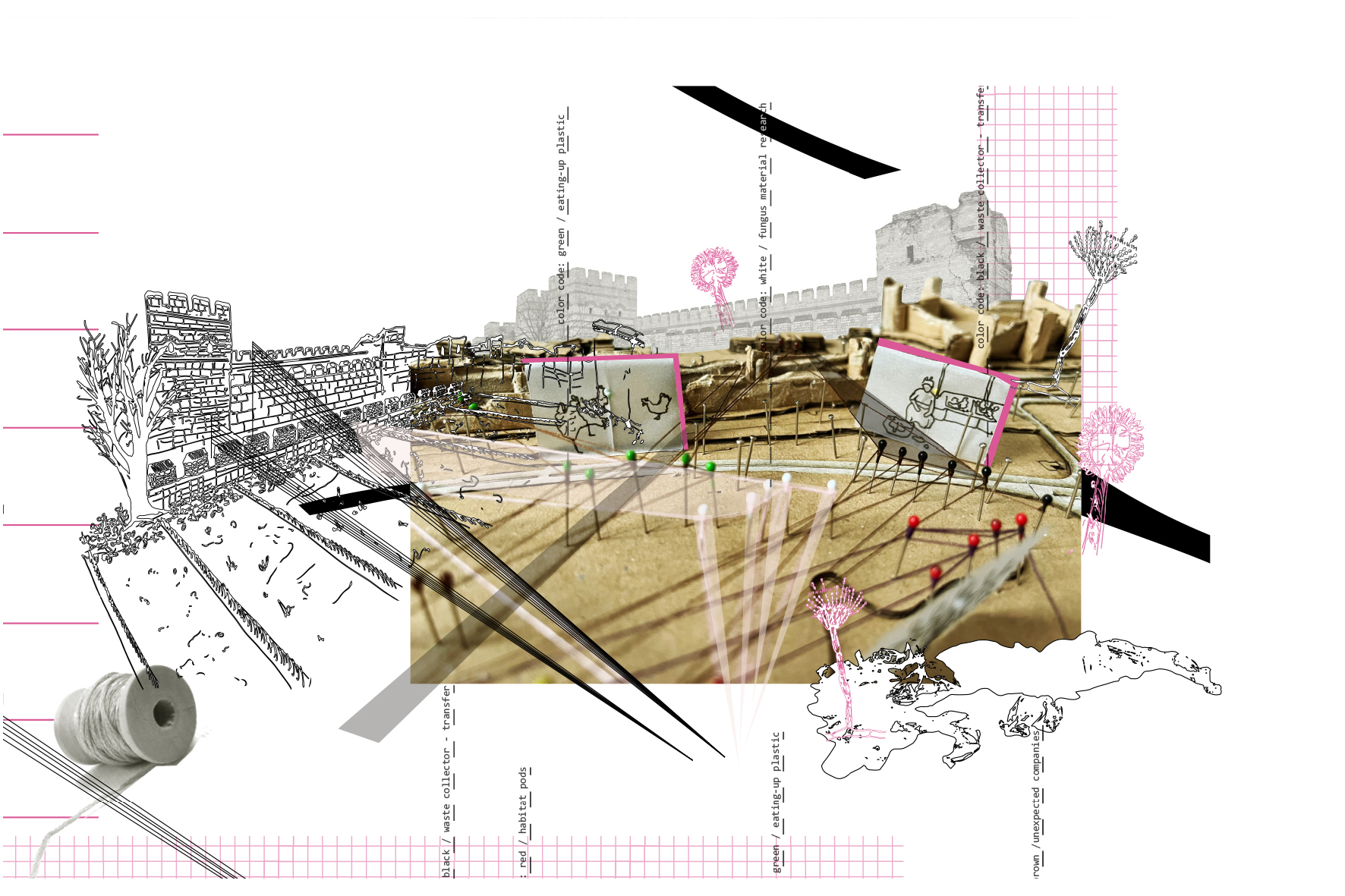

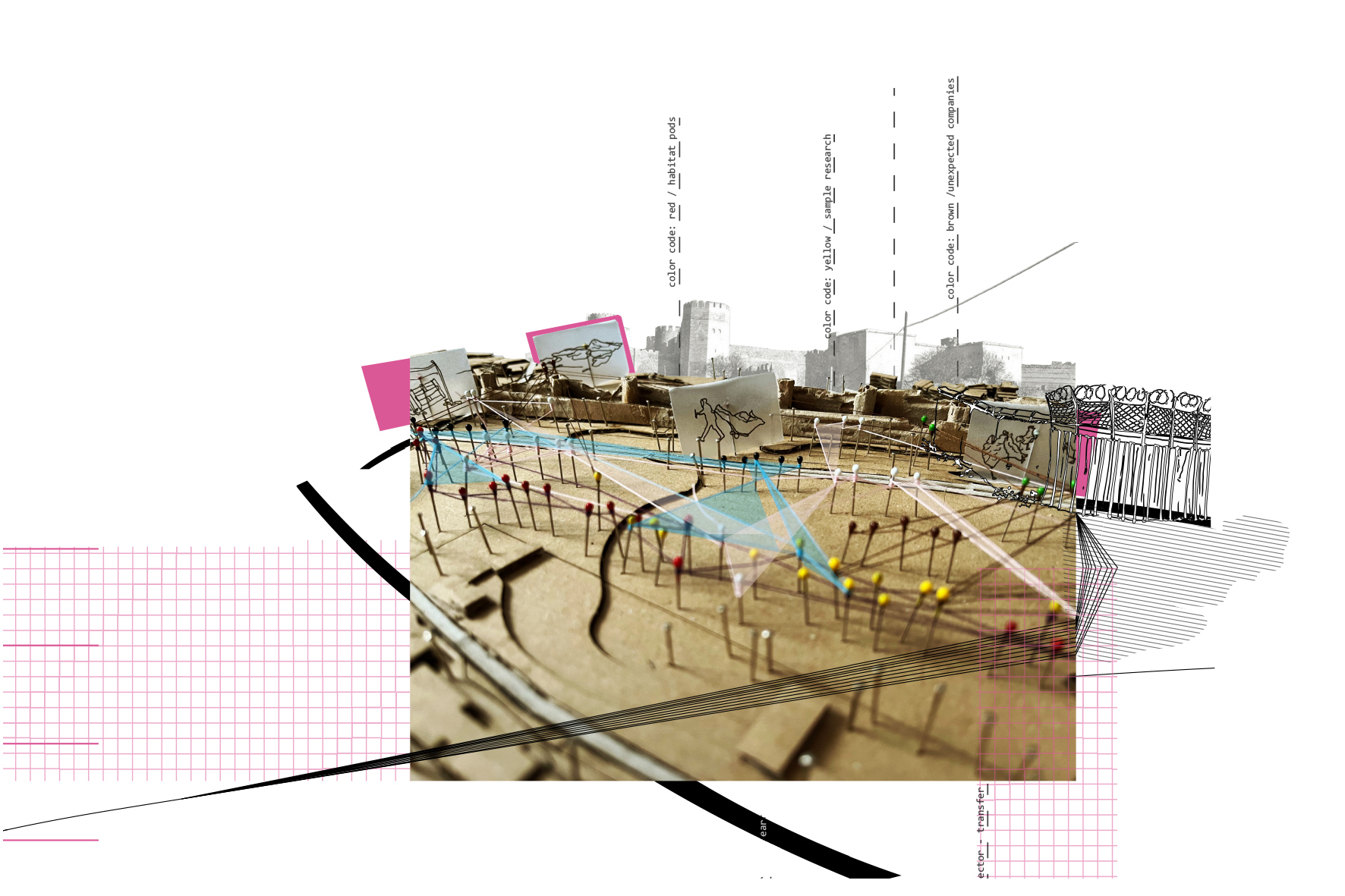

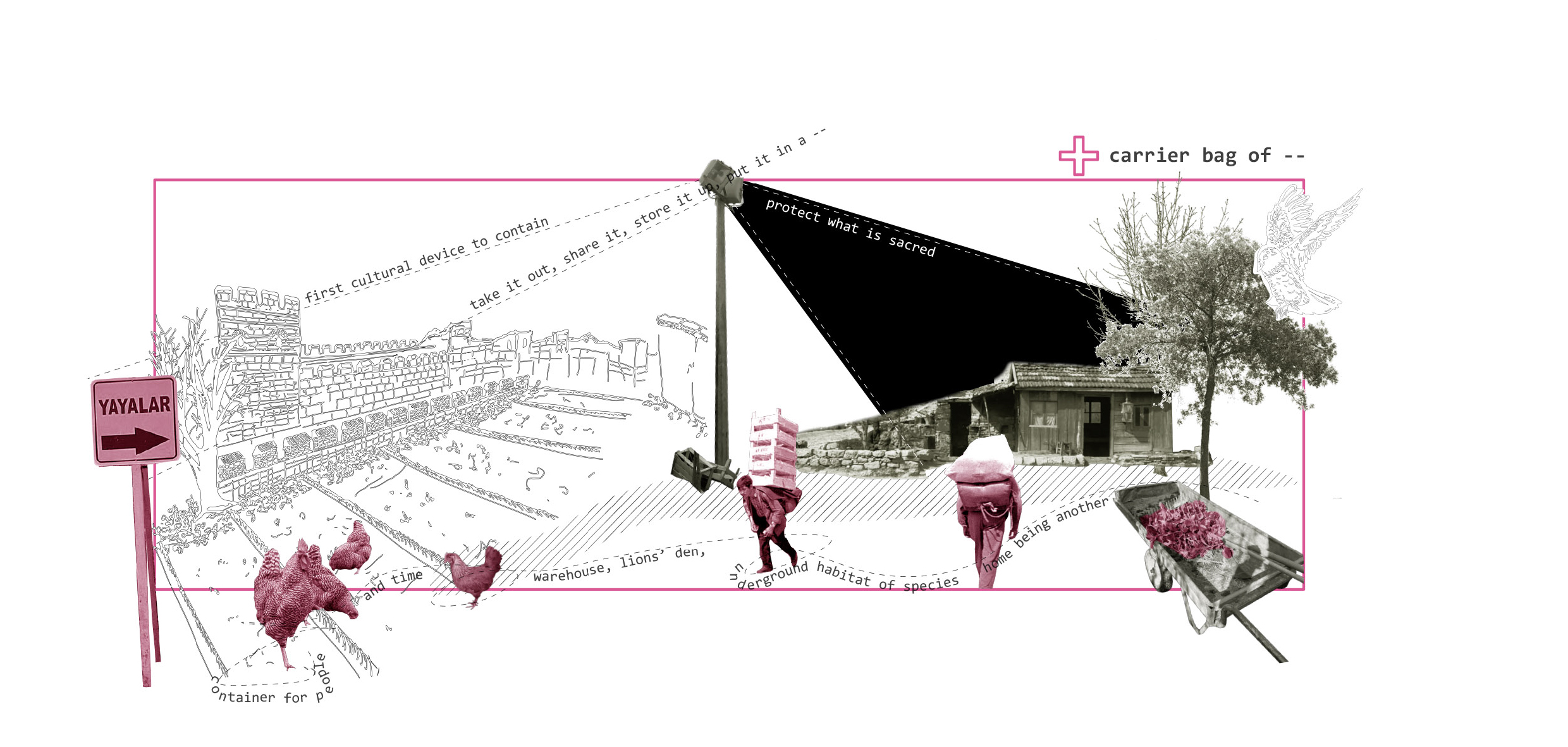

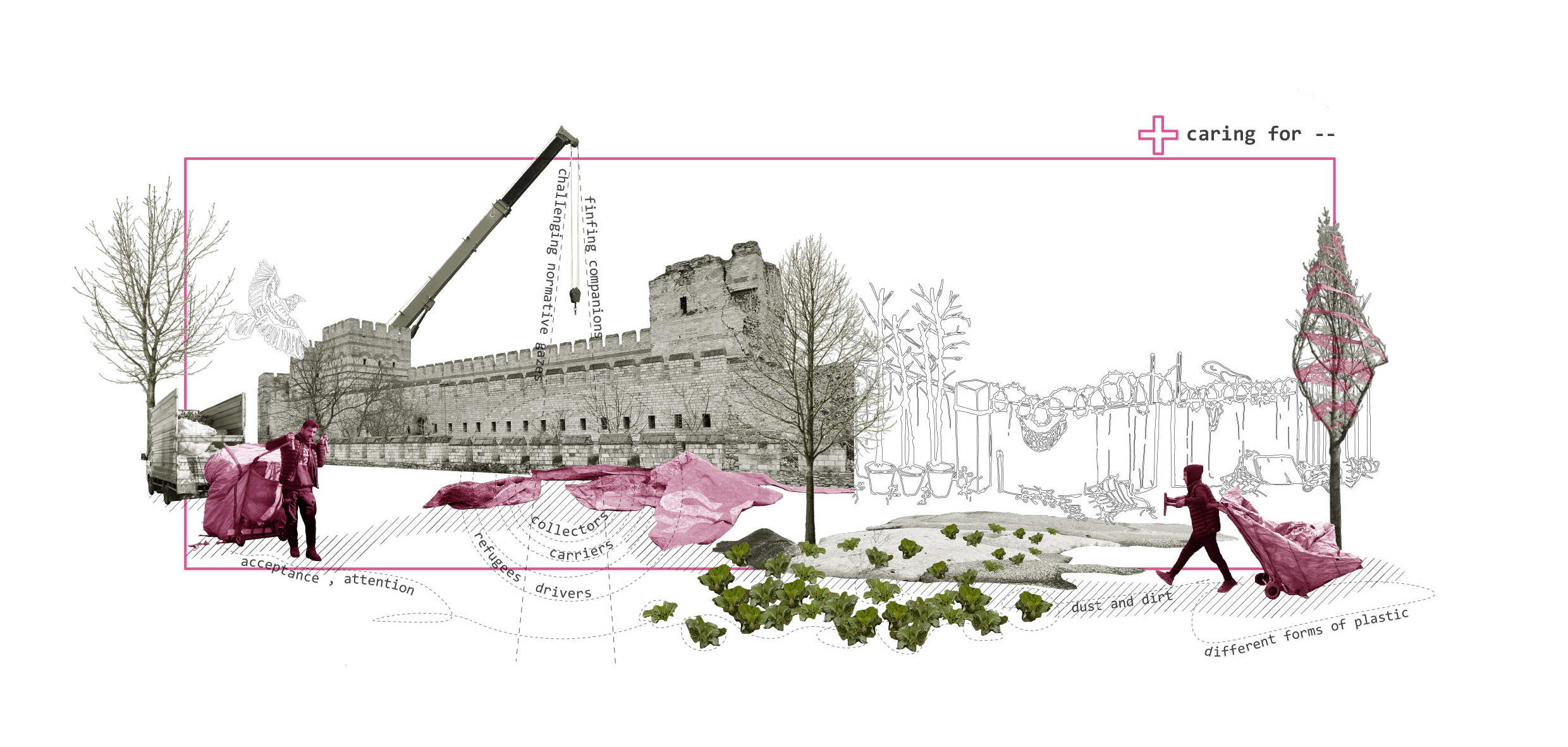

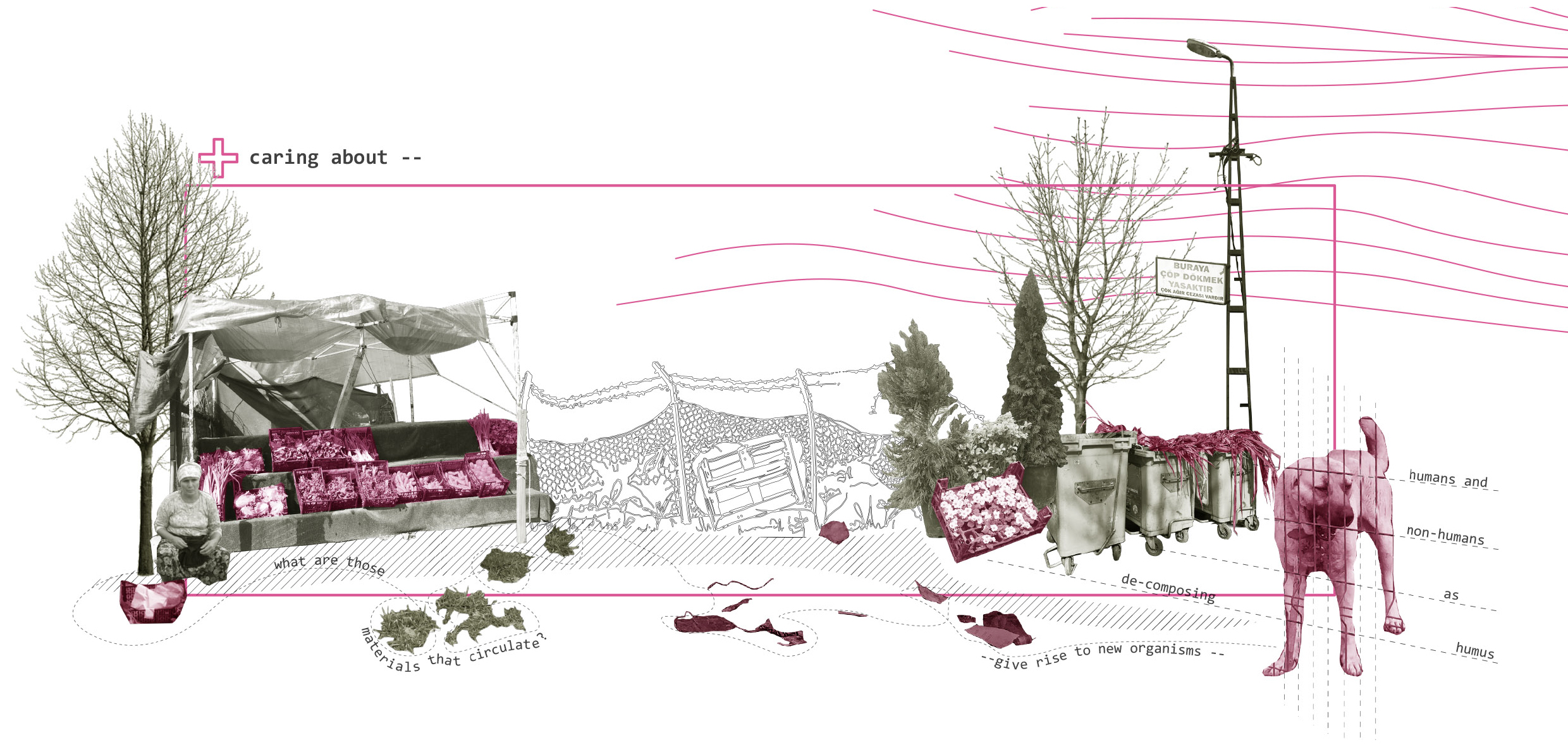

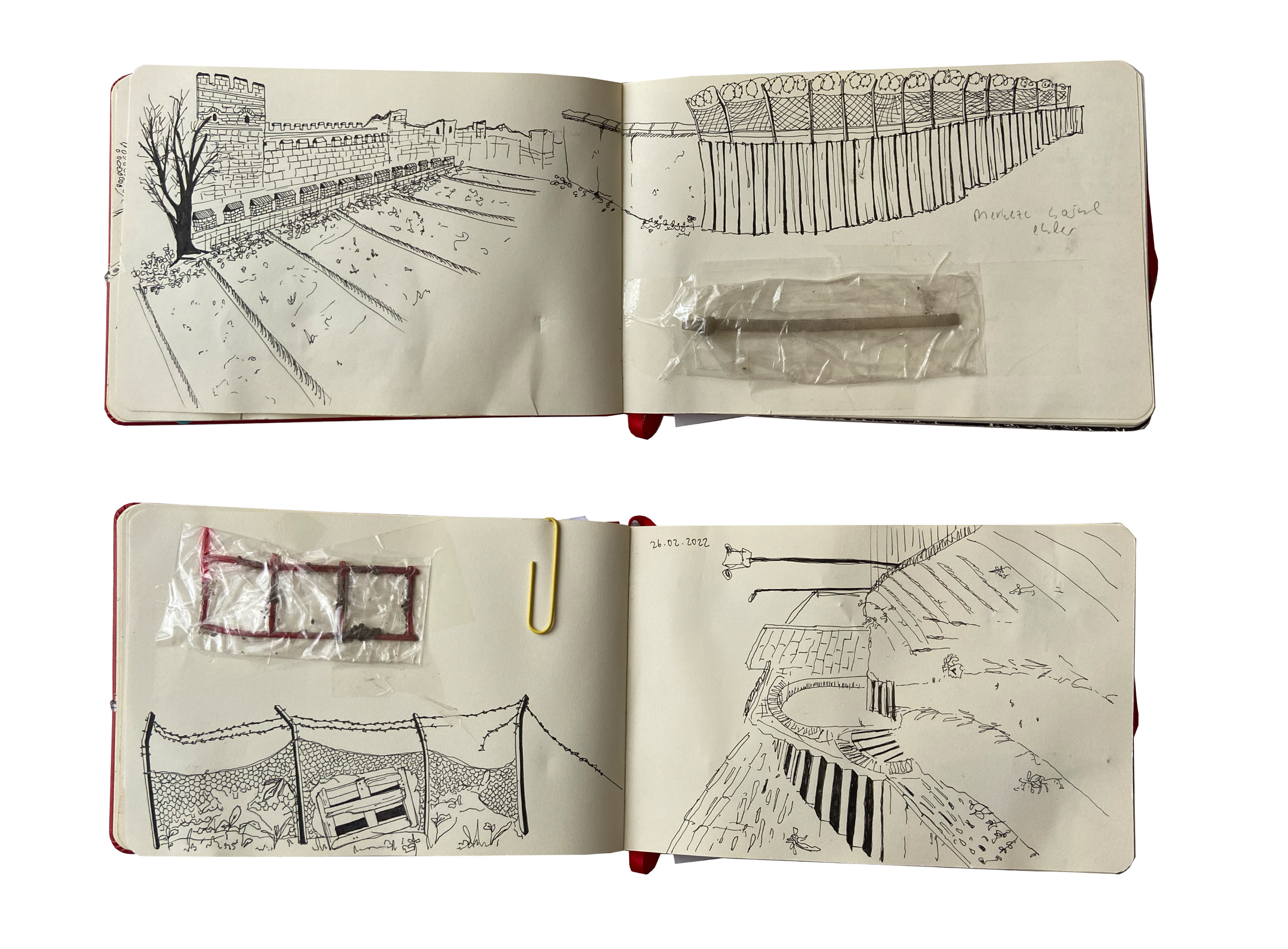

The Yedikule Gardens (Yedikule Bostans) hold a rich history, dating back to the 3rd century, supplying food to the city through continuous production. When considering the broader implications of food supply chains and the soil cycle, we can also reflect on transportation routes and the material forms of plastic. This observation suggests that we are living in a “Plasticocene” period within the Anthropocene. Ironically, even though the Yedikule Gardens are a vital green space in the city, the soil—ancient and filled with life, memories, and stories—is being polluted by the use of plastic crates, carrier bags, and rubber ties for storing, sharing, and transferring its produce.

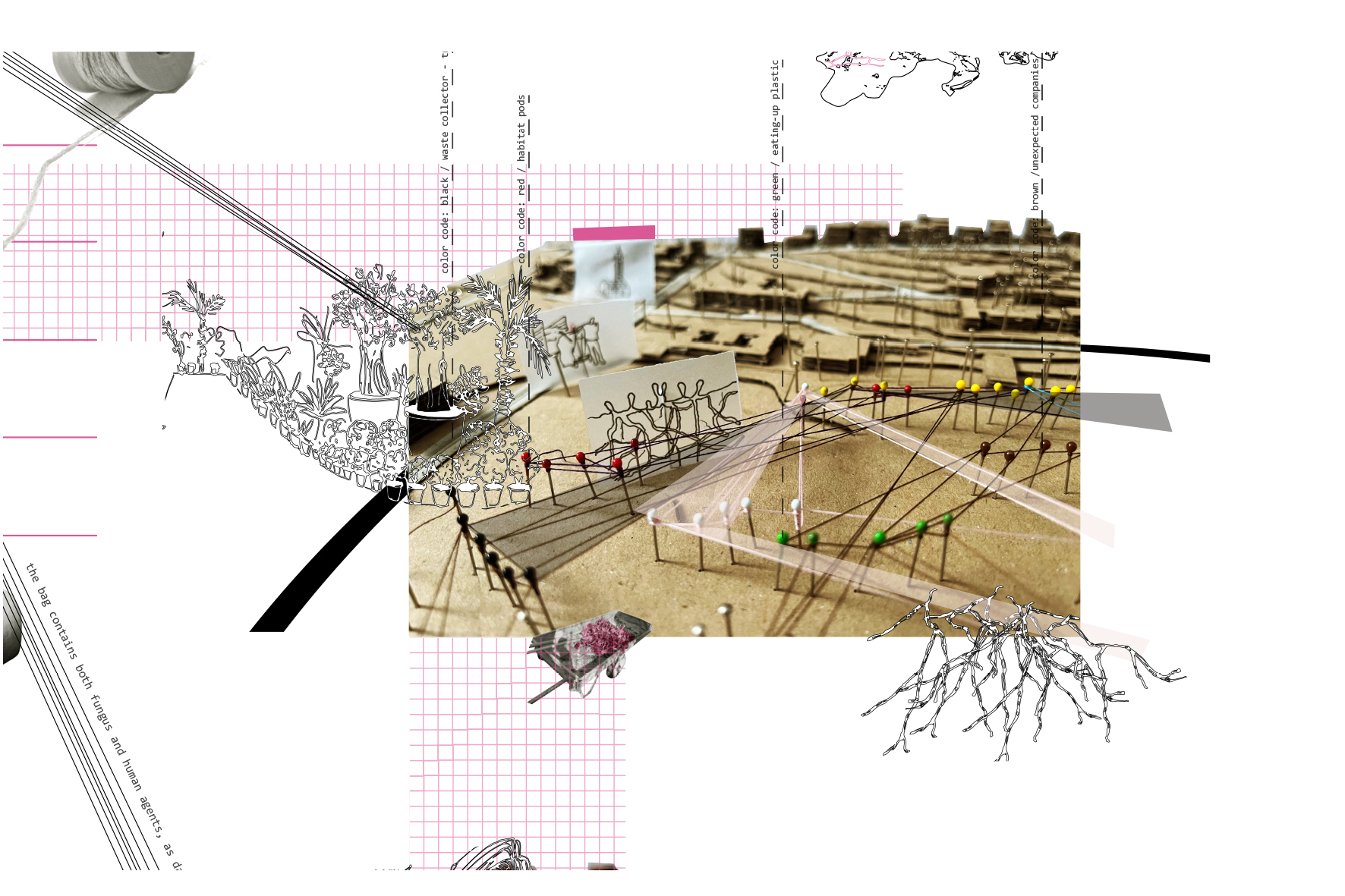

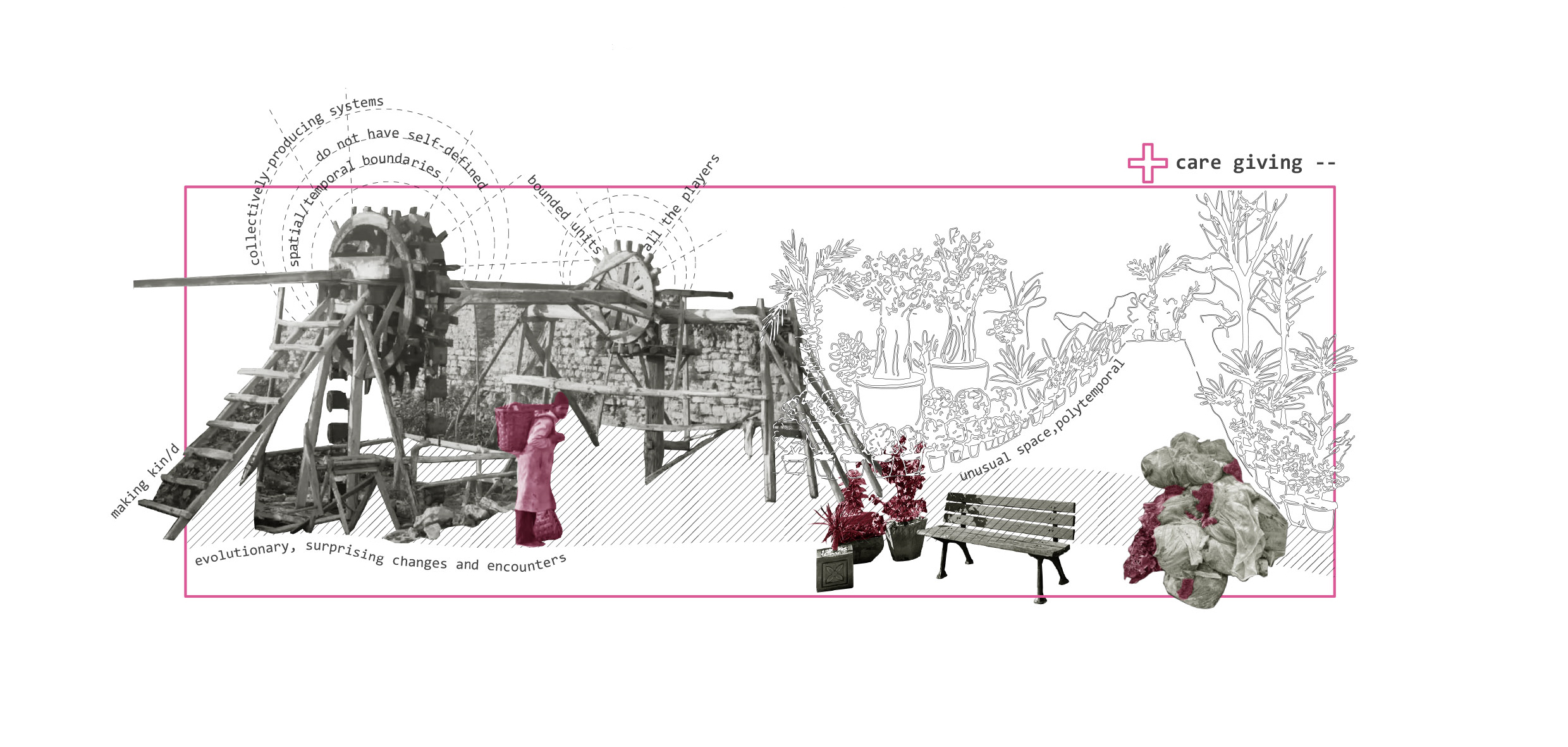

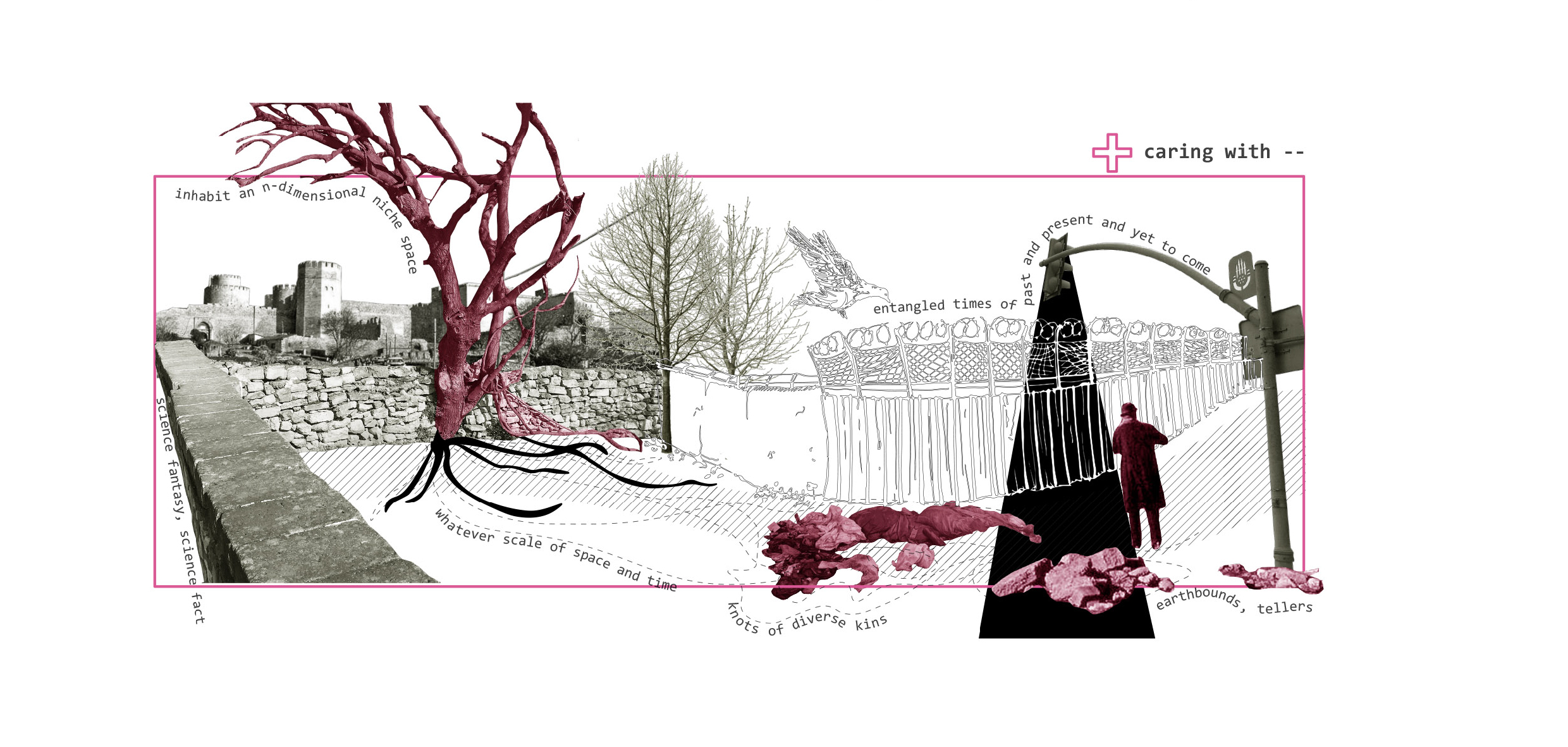

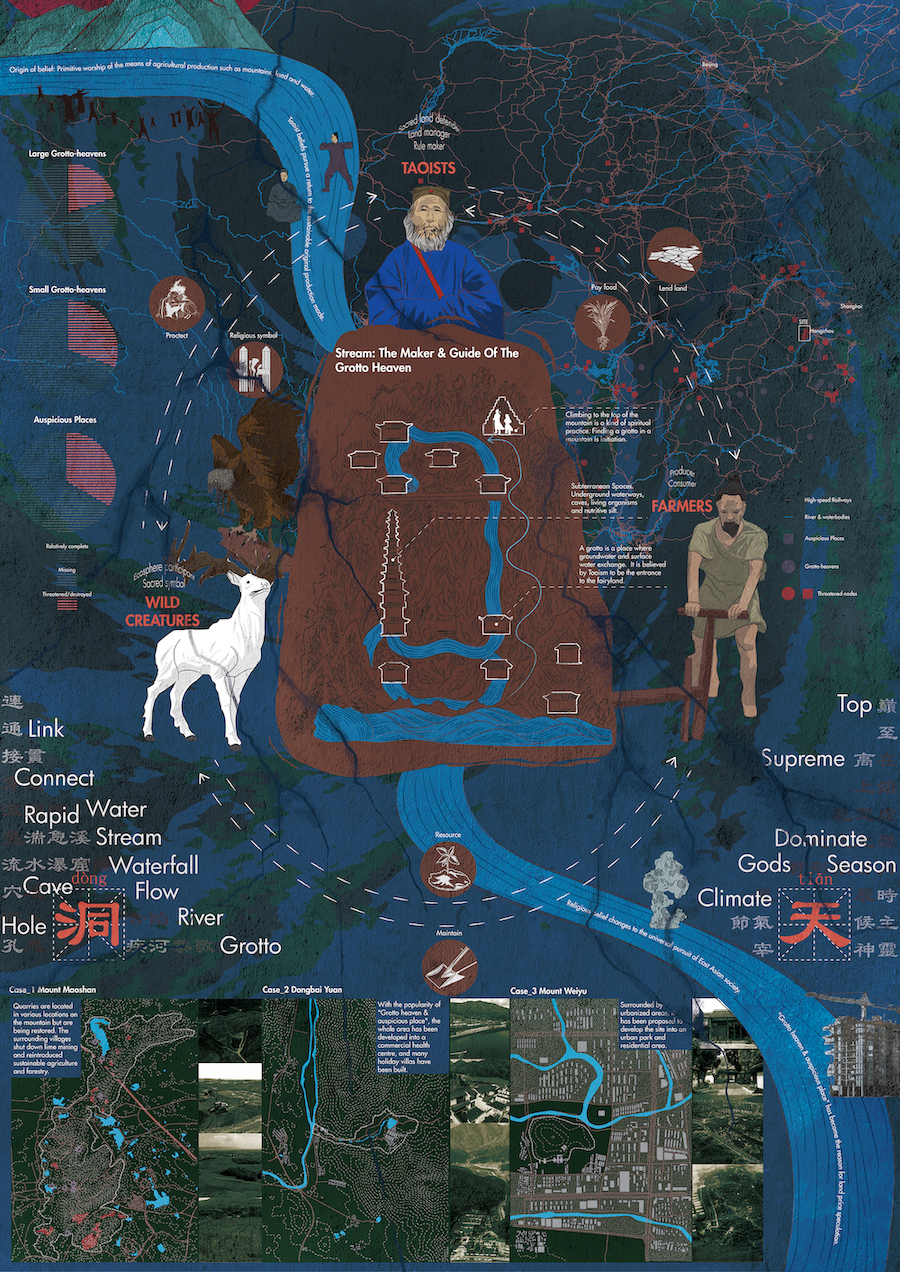

These unconscious actions affect not only the present but also the past and the future. By deciphering the relationships between the human and non-human agents of the Yedikule-Balıkçı area, we uncover a complex web of life, experiences, time, and narratives. To care means to shift our usual perspective and try to see things differently. Here, the carrier bag is both a metaphor and a literal object. The earliest human tool, a carrier bag, was used to store, share, and carry things. In the Yedikule Gardens, it remains the most commonly used tool to supply food. Moreover, the Yedikule land walls act like a carrier bag, having stored not only gardening tools and produce over the centuries but also prisoners, lions, treasure, soldiers, arms, corn, and stories.

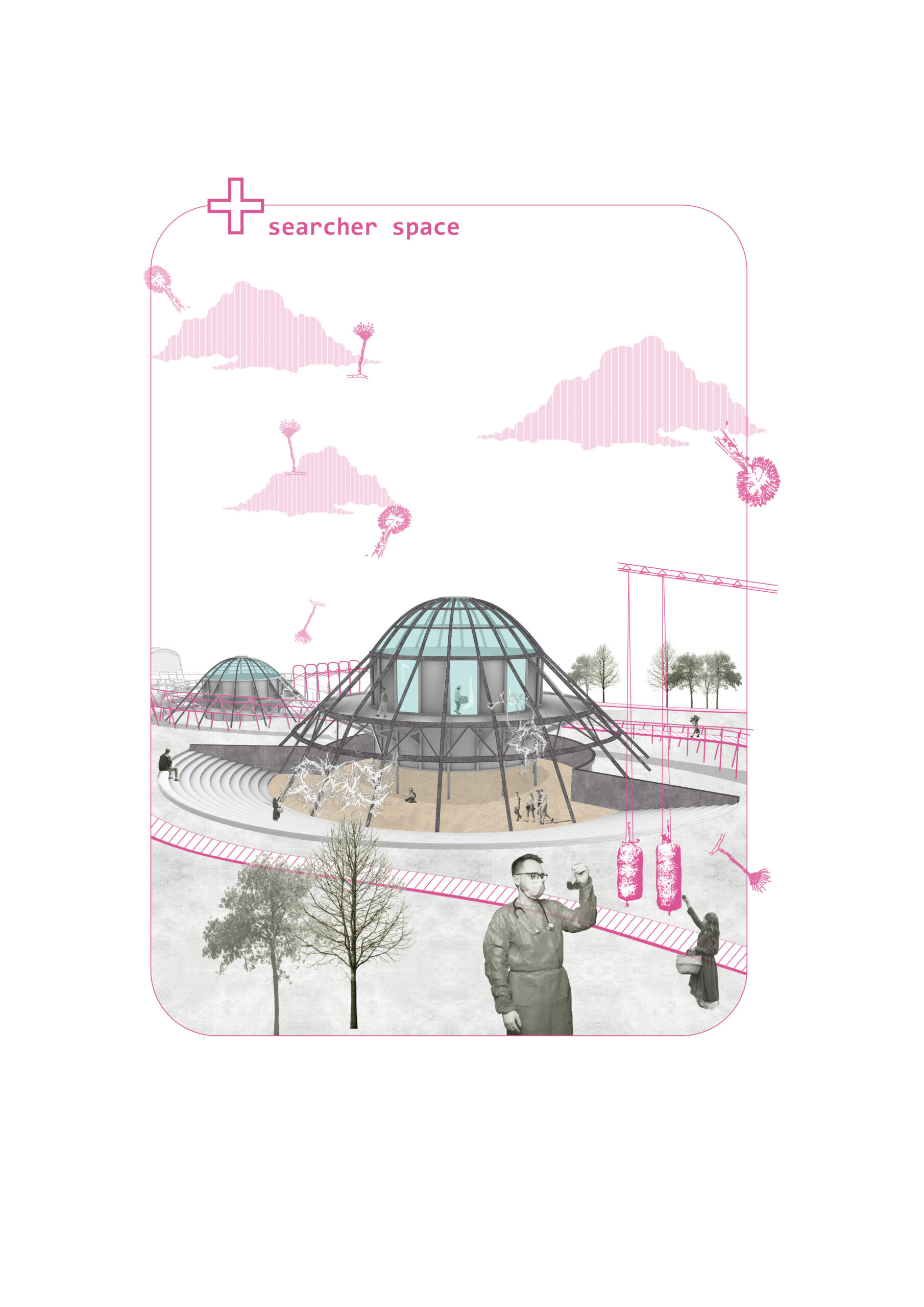

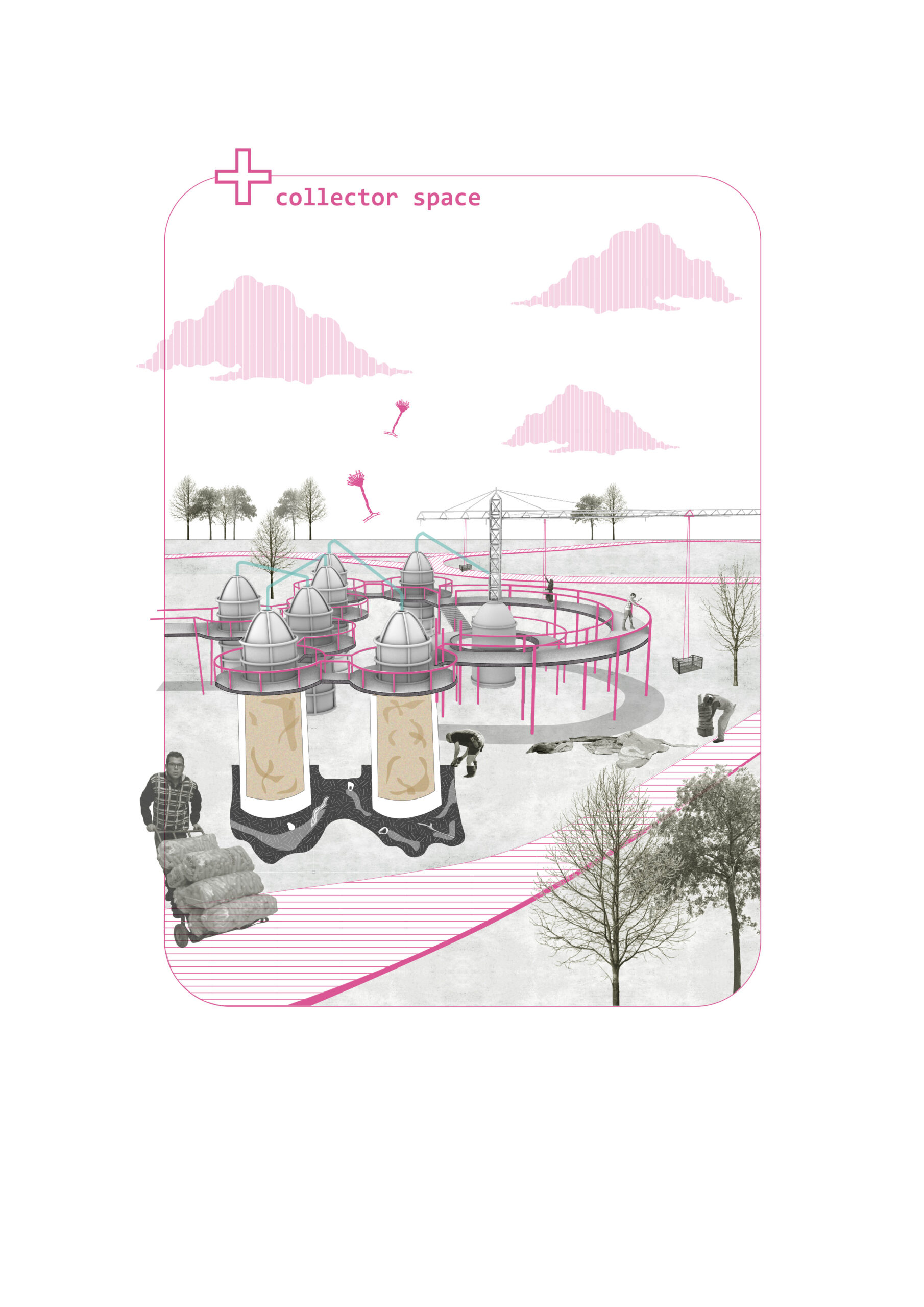

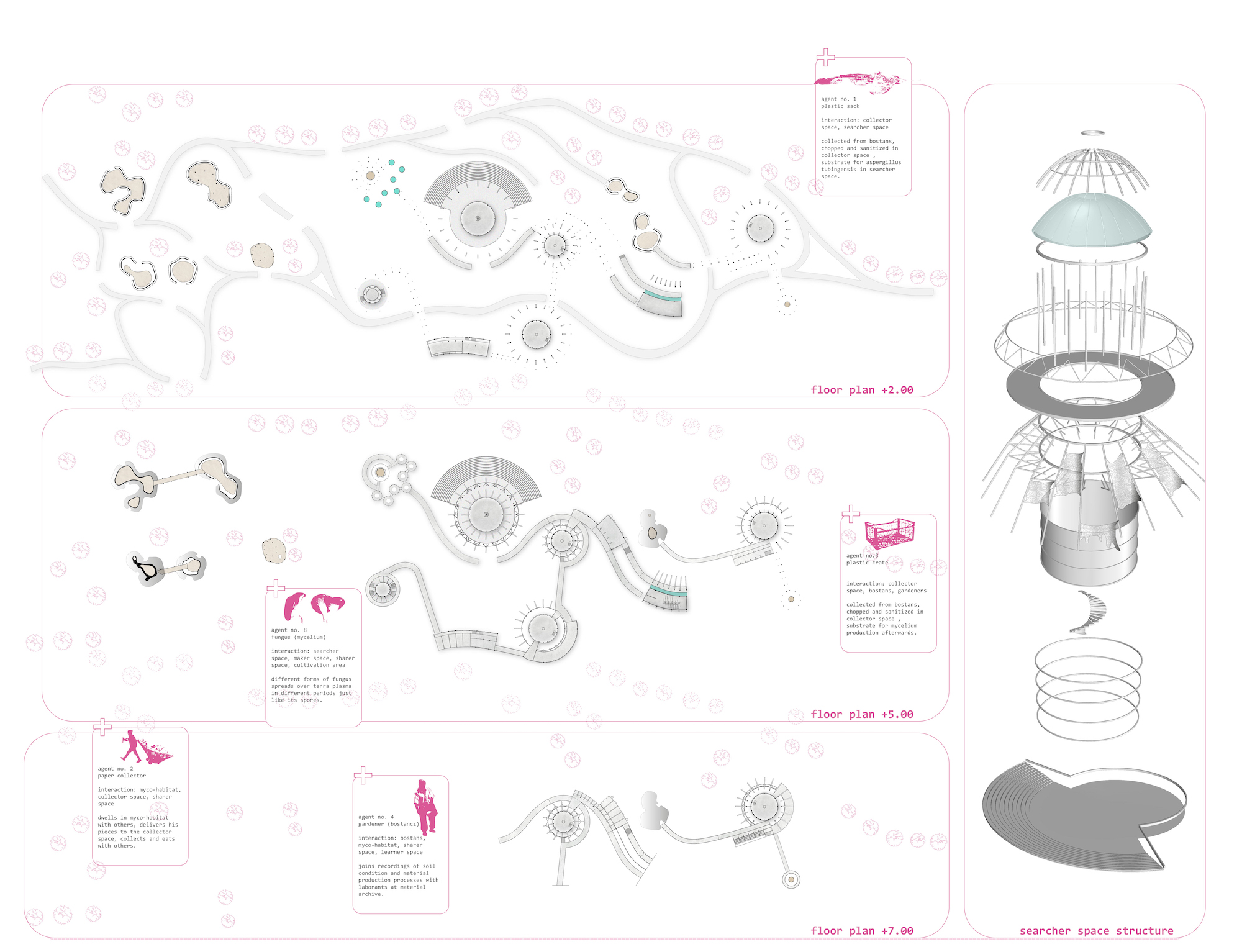

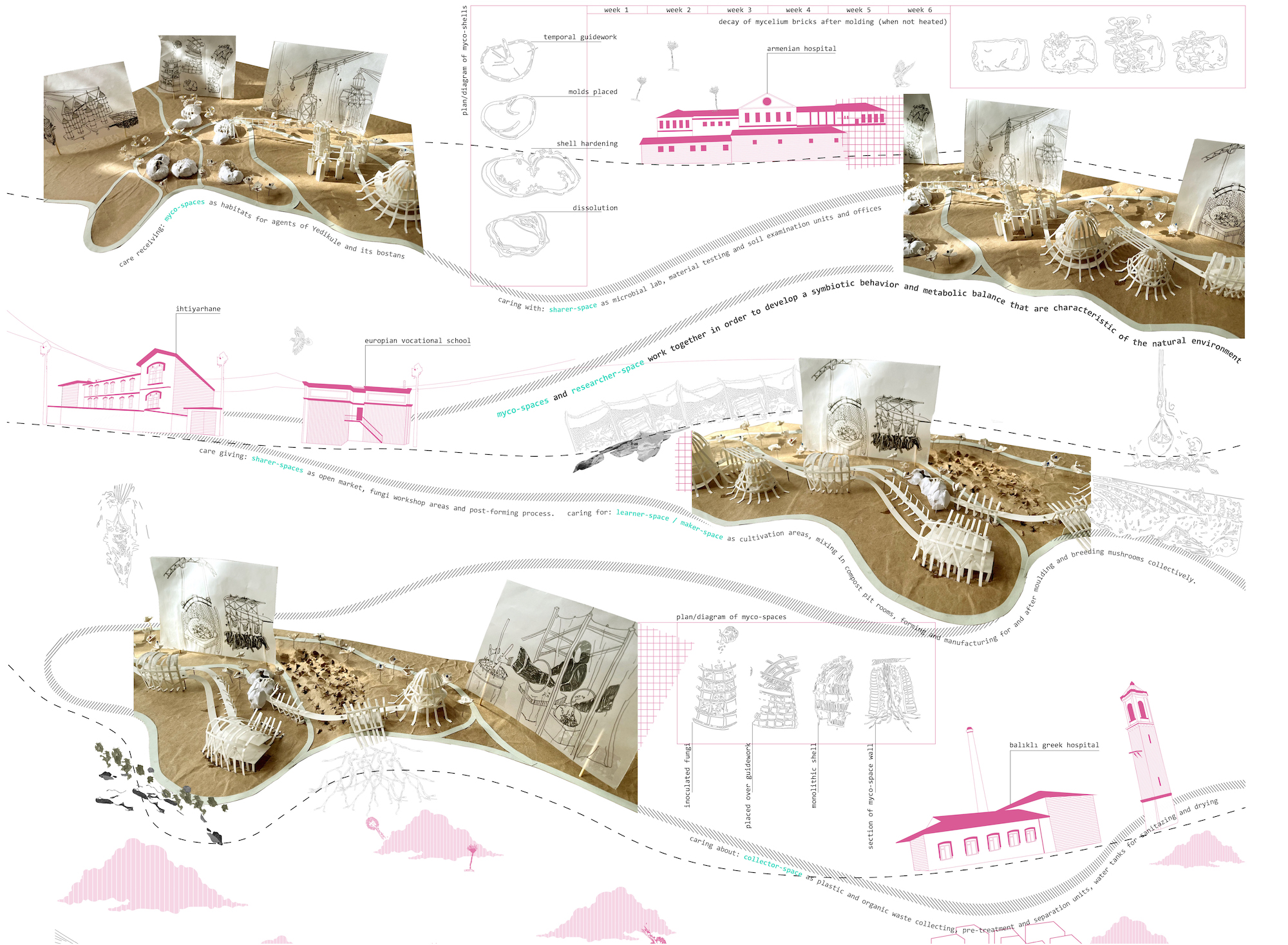

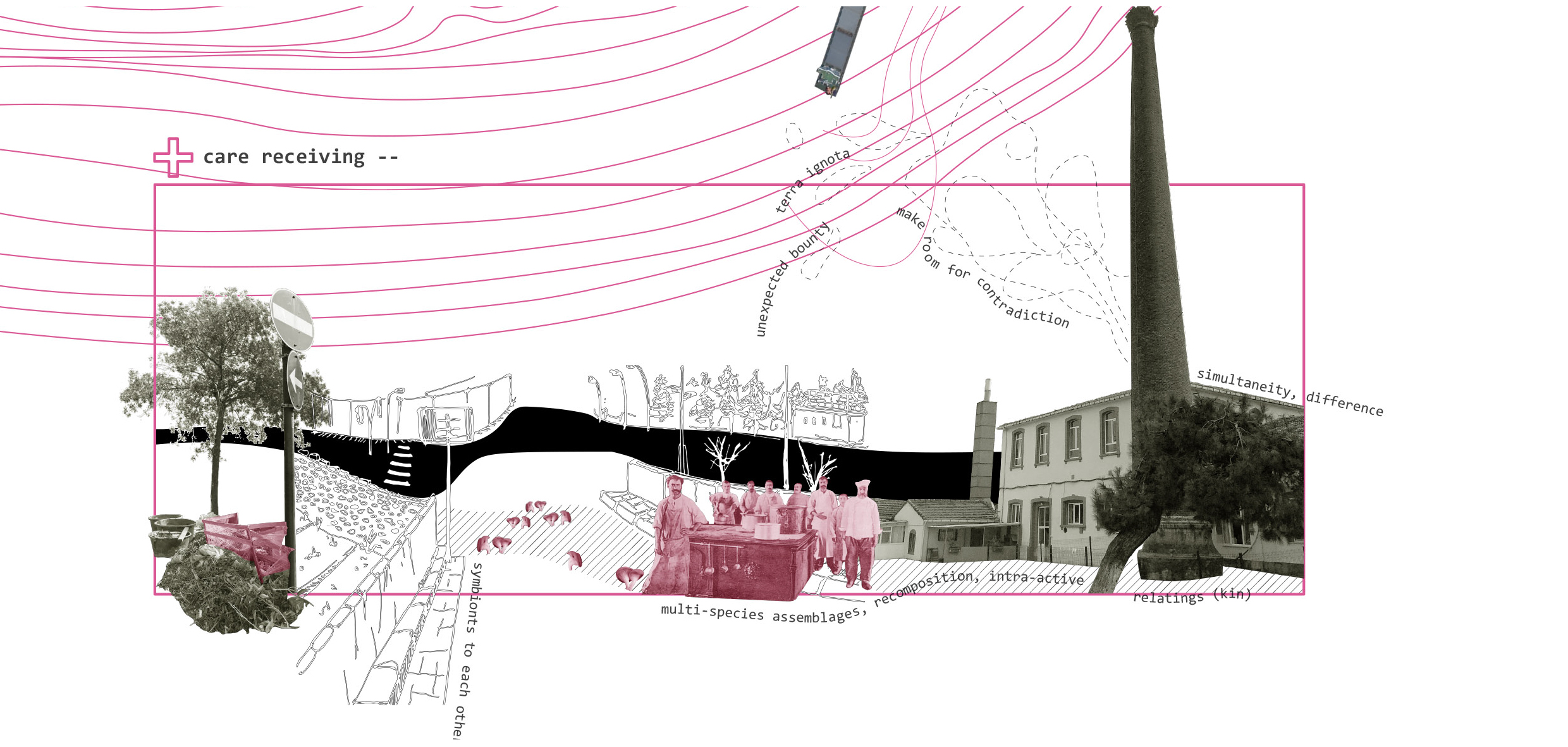

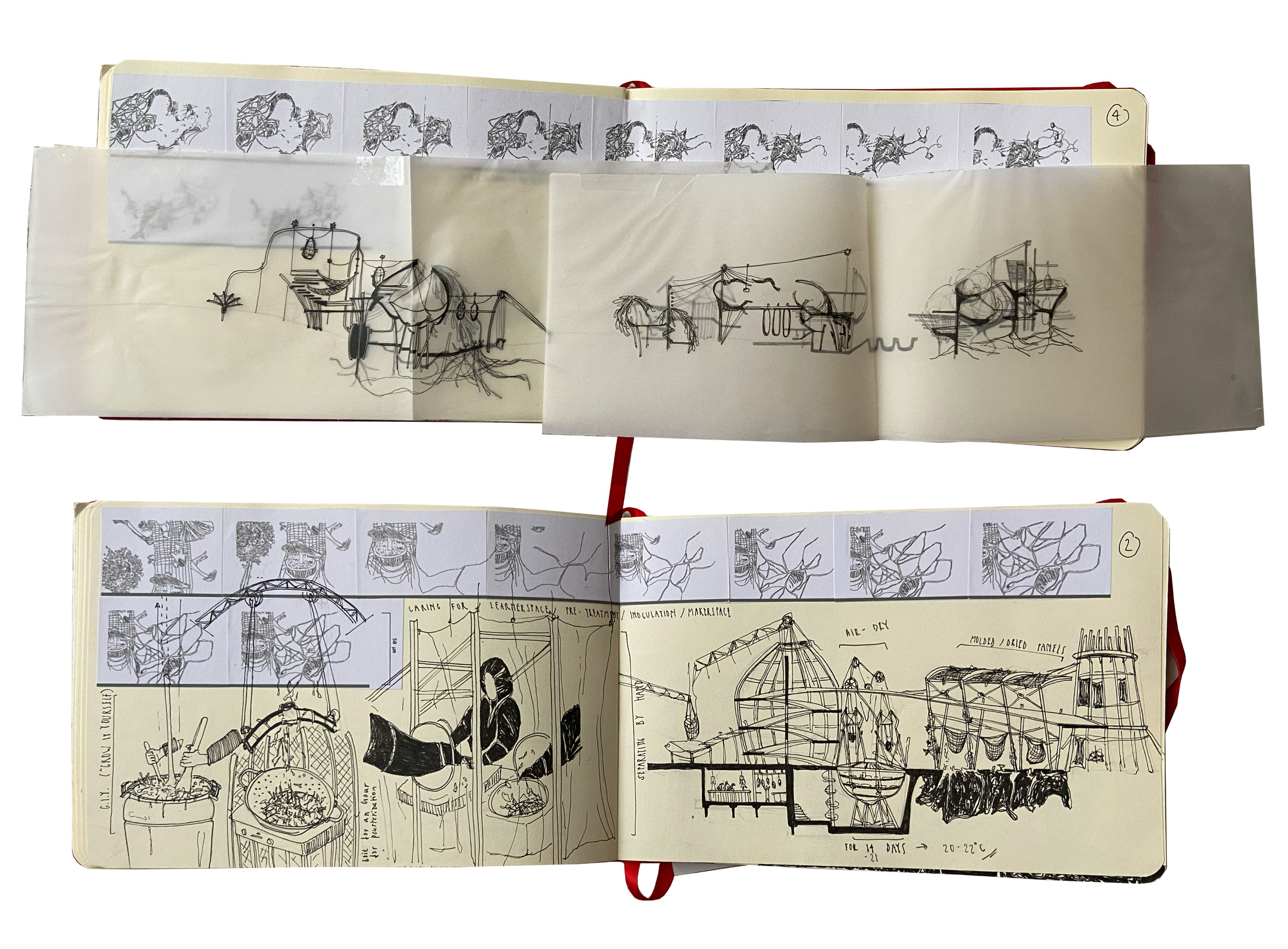

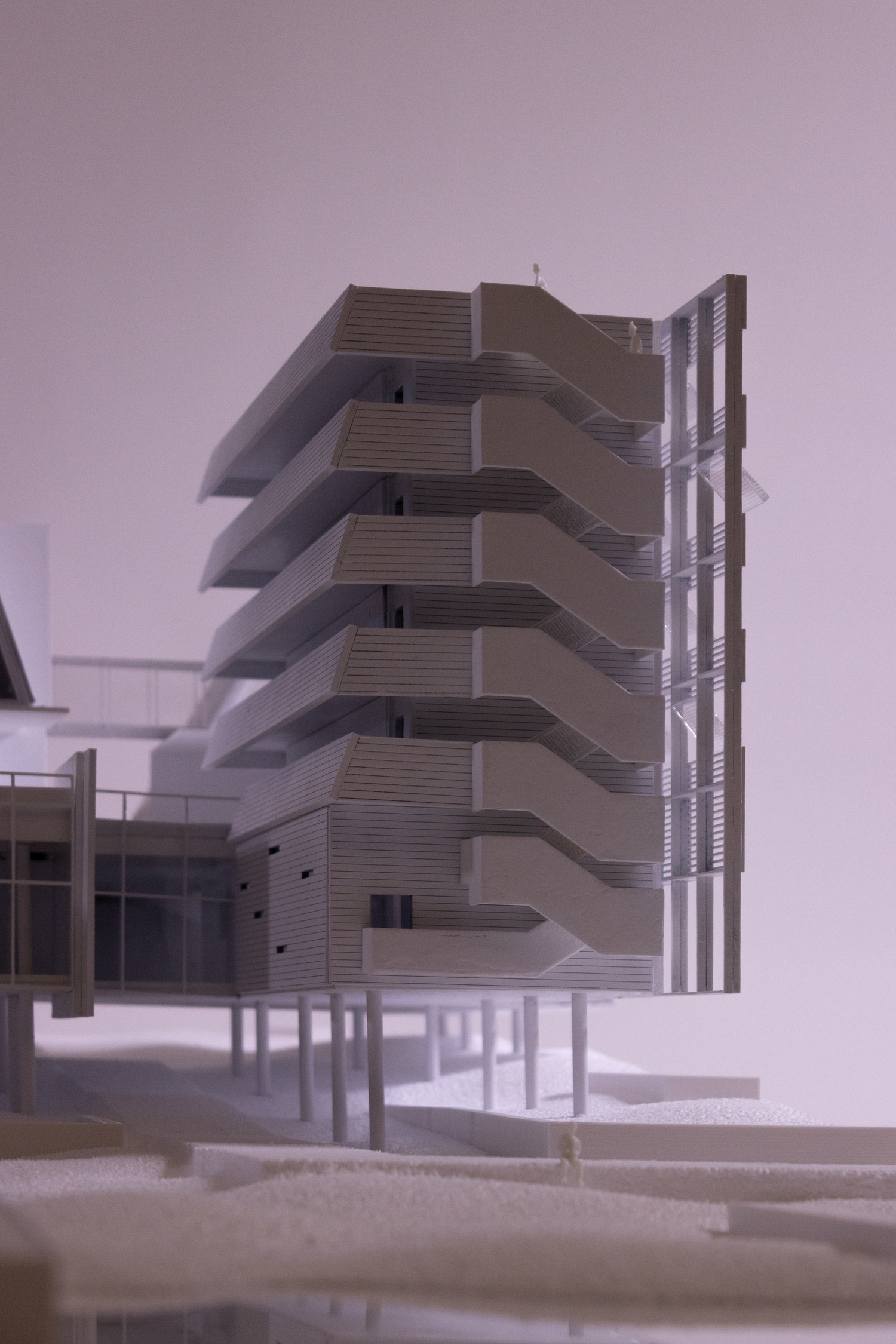

Terra Plasma+ is an open laboratory where new possibilities for experience and knowledge can be explored. It can only be fully understood when approached with care. A scene can only be observed and generated at a specific time. Terra Plasma+ is formed around the carrier bag metaphor of Yedikule, which has existed since the dawn of time. This bag transcends scales, realities, and life cycles, holding things equally to later take them out, eat, share, store for the winter, put into a medicine bundle, or transform into new forms of randomness. The Yedikule land walls have served as a carrier bag, holding weapons, soldiers, prisoners, lions, maize, food, gardens, gardeners, secrets, stories, and memories. The carrier bag of Terra Plasma+ holds ancient soil, the healing spirit of Yedikule’s waters, special fungi, spores, organic waste from nearby hospitals, plastic, refugees, paper collectors, carriers, cockerels, respect, equality, and most importantly, unexpected companionships.

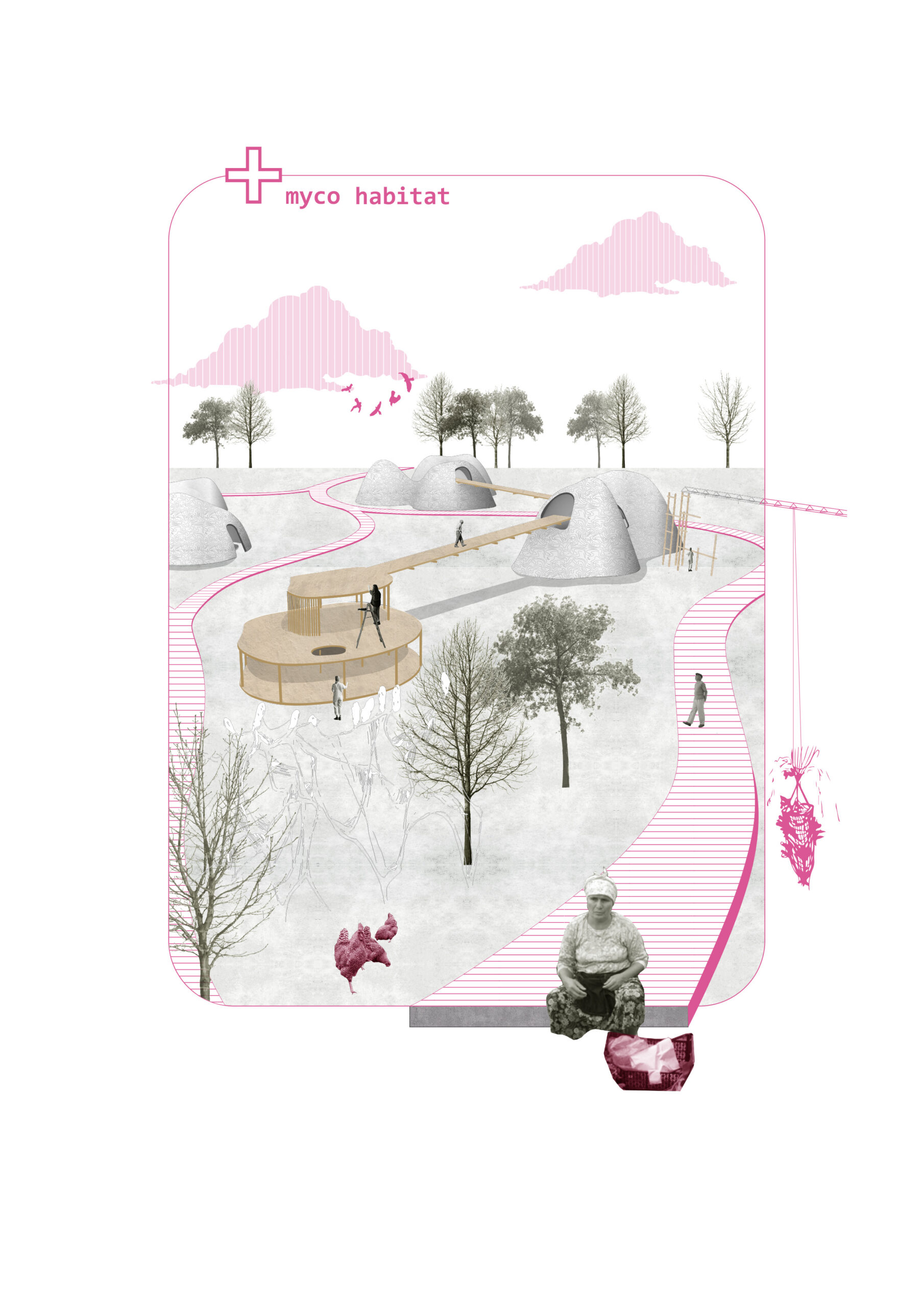

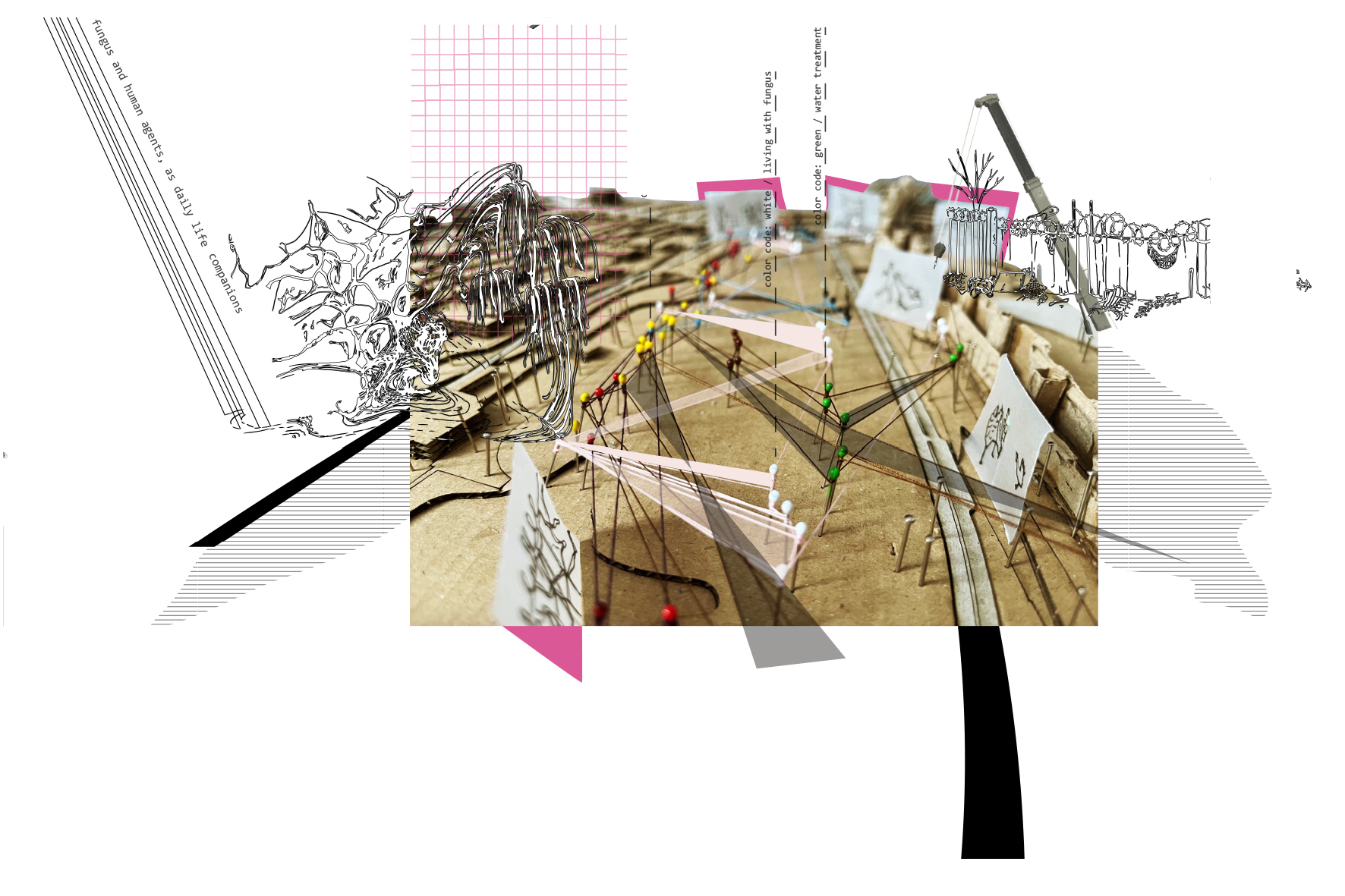

The interconnected relationships within this project create surprising alliances. Since a researcher’s lab is also their living space, it’s possible for them to encounter material providers, like paper collectors or gardeners, or those growing mushrooms or dining in the collective hall. When the growth process is uncontrolled, living pods will become temporary, shared by mushrooms and the various inhabitants of this space of equality.

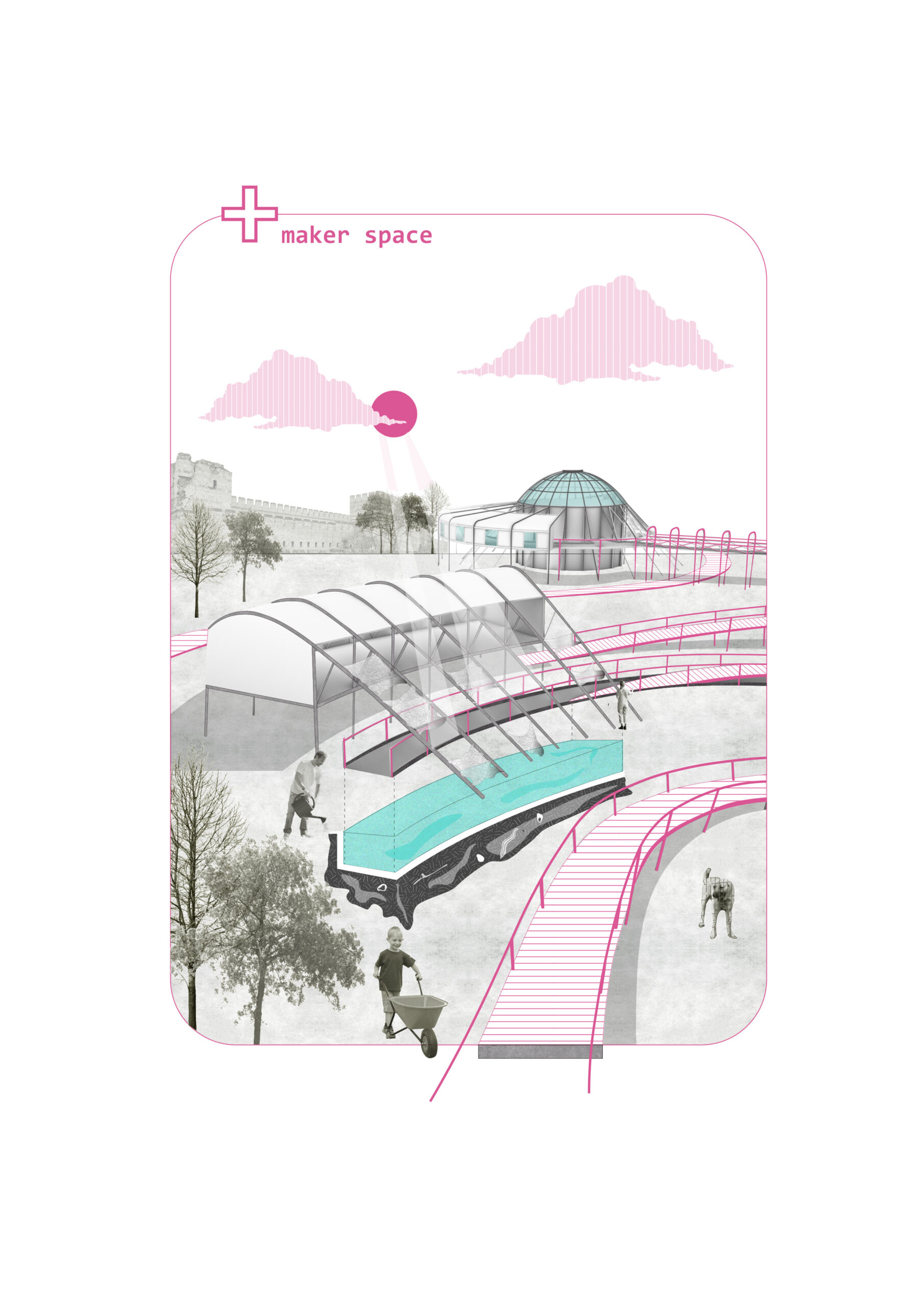

Drawing an analogy to the smallest structural unit of the carrier bag, the roots of plastic-eating fungi (mycelium) could offer strategies for researching new building materials and water purification in the area. By not segregating the different agents but rather allowing for encounters and equality, the research lab could transform into a habitat where paper collectors are part of the community. The practice of growing fungi can become part of everyday life, reflecting a modern interpretation of using all parts of an animal in Yedikule in earlier times—skin for leather, waste for gardens, meat for butchers, and money for trade. Through this analogy, plastic materials (like crates, rubber, and carrier bags) could be consumed by fungi, transformed into new materials, or used to purify water. By doing so, the carrier bag fosters kinship among the agents, offering them a more equitable life.

Caring through a shifted perspective can create an opportunity to see what lies hidden right beside us.

References:

- Fisher, E. (1979). Carrier Bag Theory of Evolution

- Le Guin, U. K., & Haraway, D. P. (2019). The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. London: Ignota Books. (pp. 149-154).

- Tsing, A. L. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press.

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Gabauer, A., Knierbein, S., Cohen, N., Lebuhn, H., Trogal, K., Viderman, T., & Haas, T. (2022). Care and the City: Encounters with Urban Studies. Taylor & Francis.

- Evren, B. (2006). Surların Öte Yanı – The Other Side of City Walls. Zeytinburnu Municipality, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Aslıhan Demirtaş, Interview: Istanbul’s Unique 1600-Year Urban Farming Tradition – Yedikule Bostans.