Landscape Architects Rise to the Challenge of Coastal Flooding

Author: Pamela Conrad

It’s that time of year again: students and their families are busy preparing for the start of school, while some of us are gearing up to step in front of the classroom.

While preparing to teach an intro course on climate, I’m reminded of why we use the term climate change and not global warming. Yes, the Earth is warming from a thickening layer of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere caused by us. But climate changes range from sea level rise to increasing storms, floods, fires, and drought, which are all negatively impacting biodiversity as well. So, not just warming.

Recent storms that battered the eastern U.S. coast and Bermuda remind us of this difference. While some communities face extreme heat, others brace for storms and rising waters, and many face multiple impacts.

Elevating flood protection was perhaps the first way landscape architects began designing climate change solutions. Many have been working on flood management for their entire career. I first engaged in this work at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers some 20 years ago. Over the past decade, my focus shifted to coastal adaptation projects, like the San Francisco Waterfront Resilience Program, Depave Park, and Treasure Island. They taught me that designing for unprecedented storms and rising seas requires a new tool bag, belt, and a whole new set of tools.

Much of our work as landscape architects focuses on designing adaptations. When designing with nature, we can create adaptations that reduce emissions and costs and increase benefits for ecosystems and communities. We’ve also learned new ways to engage community members and support them in gaining resources for self-determination when facing these risks.

Designing for Rising Waters

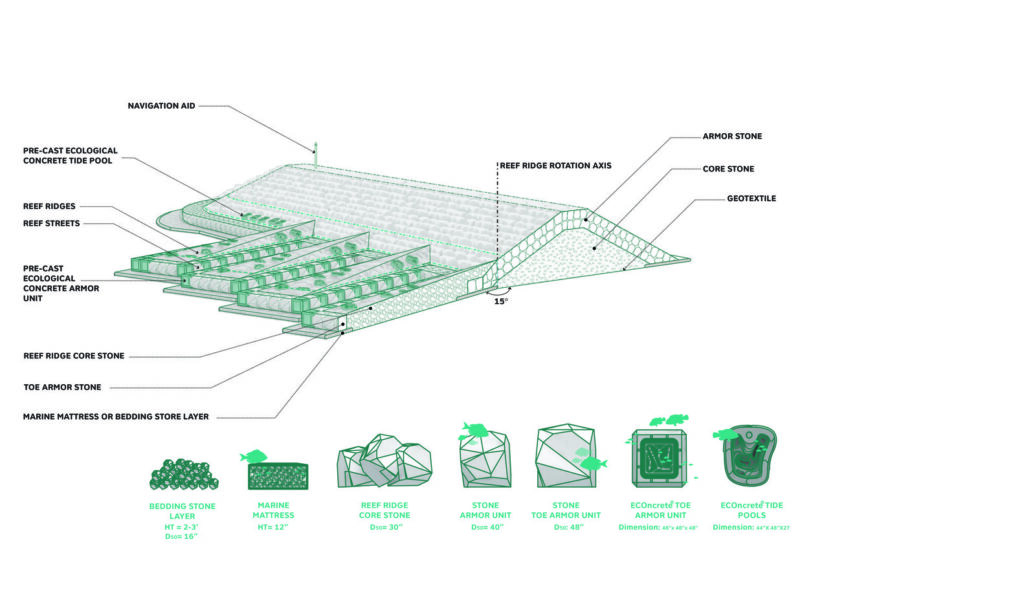

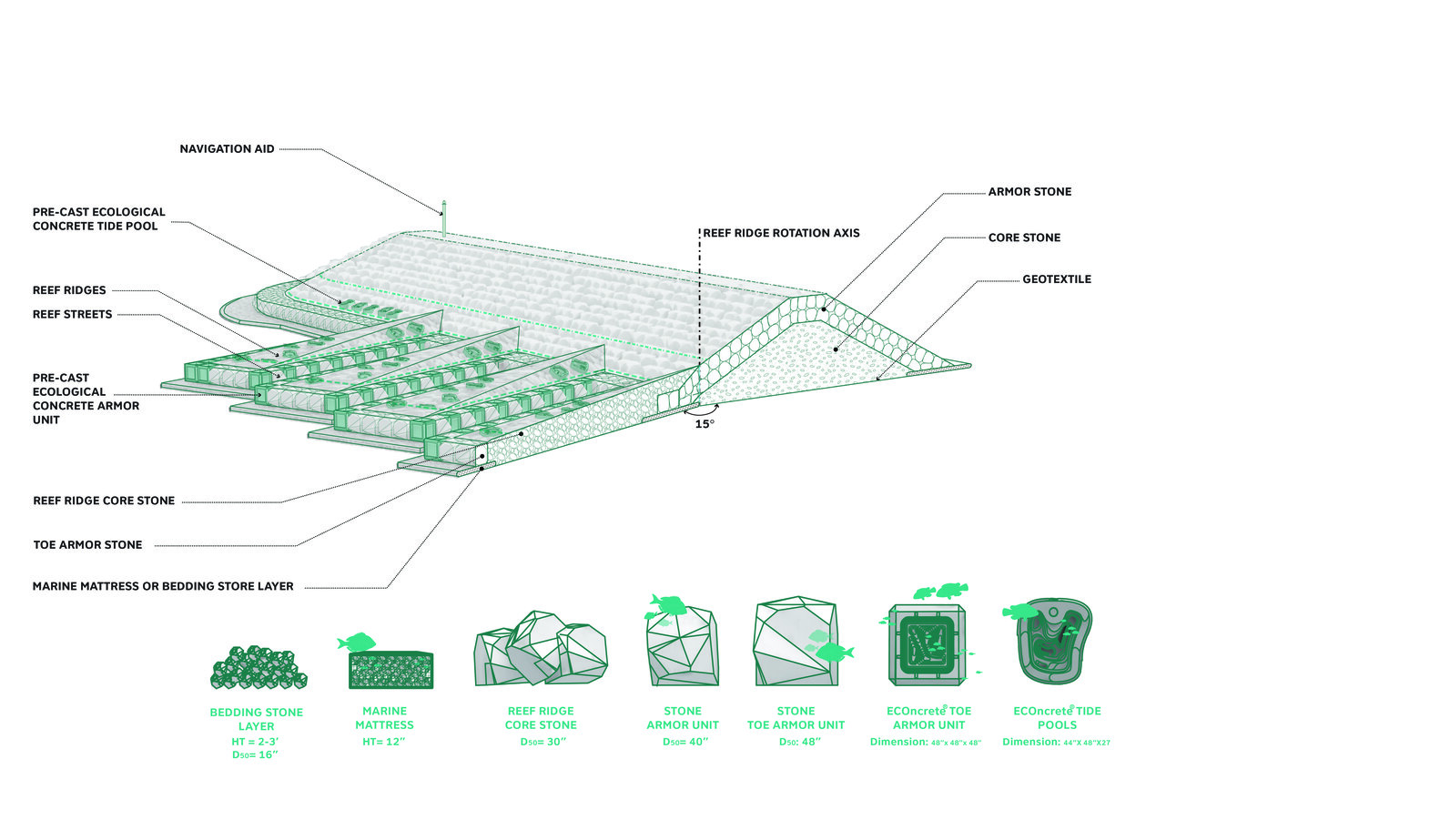

For the Rebuild by Design competition in the tri-state area, which was a response to Superstorm Sandy, the landscape architecture firm SCAPE developed the clever living breakwater technique. It’s an offshore approach that reduces the impact of intense waves on communities during coastal storms while benefiting ecosystems. Pushing beyond just flood protection, it transforms a typical breakwater approach into an aquatic environment supportive of marine life, including oysters. It also serves as a habitat and refuge for larger species.

In addition to designing this physical and non-traditional infrastructure, SCAPE spent countless hours documenting their approach and negotiating with governments at all levels to get their idea approved. This form of advocacy takes devotion but is required to innovate in this challenging and changing climate.

Engaging Communities

In San Francisco, a city renowned for its inclusion and celebration of diverse voices, the commitment to openness can sometimes result in lengthy processes and, occasionally, lead to inaction. The team at landscape architecture firm CMG – Kevin Conger, FASLA, in particular – realized that a new model of participatory design was needed to rise to the challenge of increasing coastal flooding.

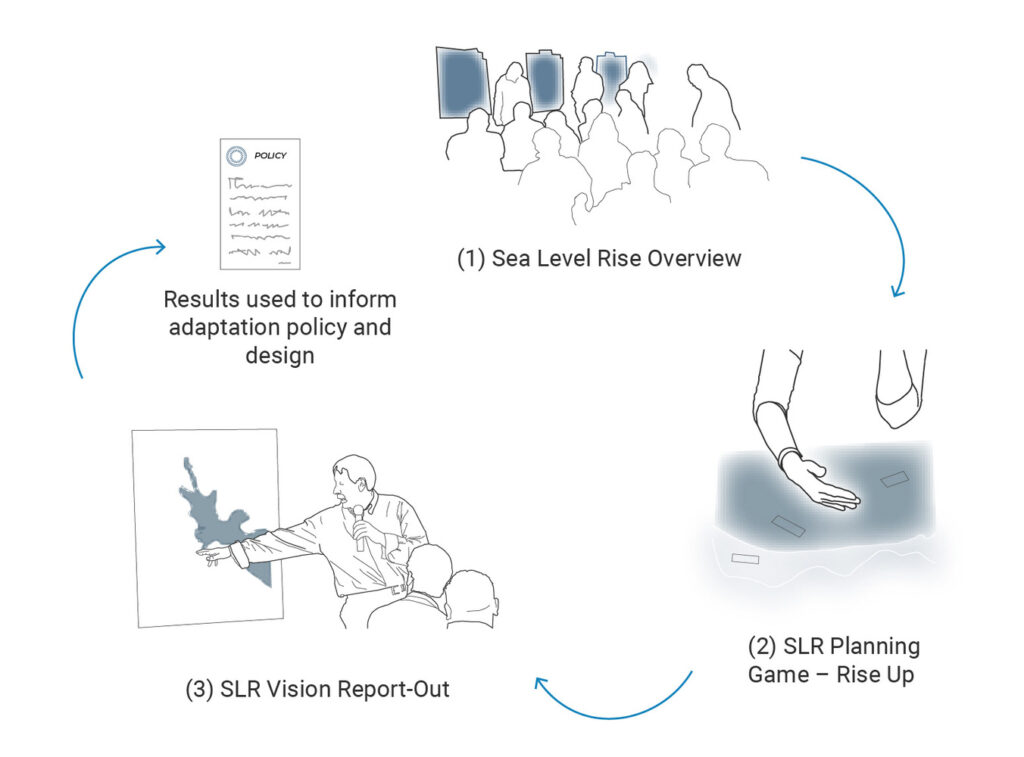

Rise-Up is a community engagement process that was first piloted in Southern Marin County and then evolved as other projects continued through our work at Crissy Field in San Francisco and with the Port of San Francisco Waterfront Resilience Program.

The Rise-Up model includes three main steps:

- Sharing scientific knowledge in an accessible way to the community.

- Gathering responses through the hands-on engagement activity called “Game of Floods” where participants use risk maps to come up with adaptation alternatives.

- Community presentations of their ideas, which ultimately move forward in the design and planning process

The role of the landscape architect is shifting to become both facilitator and listener. This enables us to support more community self-determination. Plans and designs can be rooted in community ideas, which they can fully champion.

One way to complement in-person or online activities is to engage communities where they are. FloMo was developed by landscape architecture firm Bionic for the Resilient by Design Competition: Bay Area Challenge. It engages communities impacted by flooding.

By transporting knowledge and resources via the FloMo van, backyard interactive learning happens at the homes of those most impacted by sea level rise. This approach creates a memorable and informative encounter that prepares those in need for the tough decisions ahead.

Enabling Underserved Communities

The harsh reality is that adaptation will not happen without funding. For historically marginalized, underserved, and under-represented communities, this is a devastating but familiar circumstance.

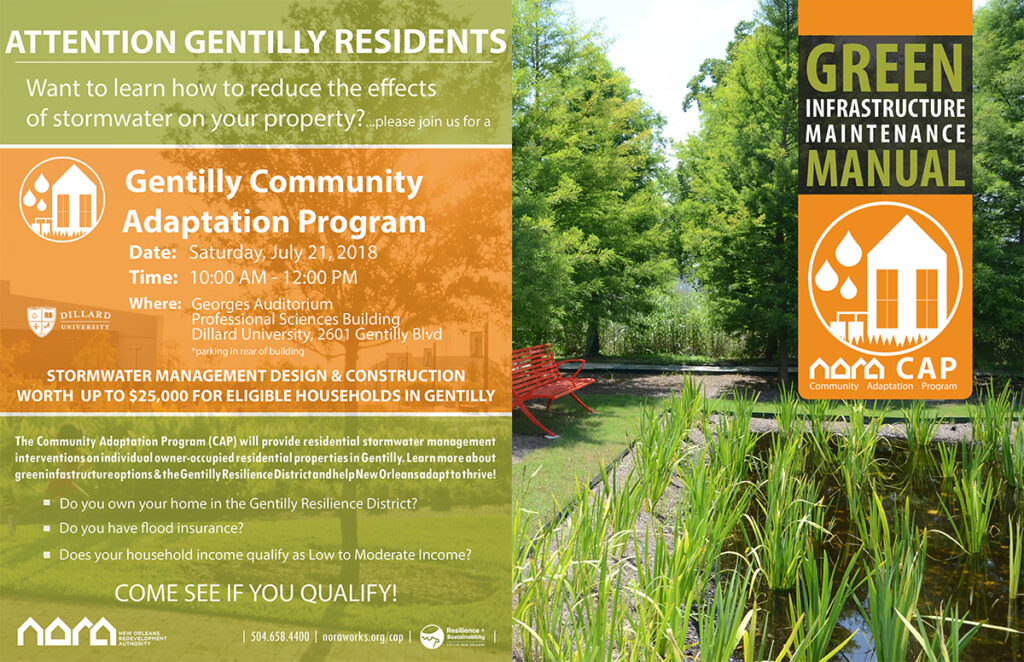

Landscape architects at Design Jones, LLC offer a model through their work in the Gentilly Neighborhood of New Orleans. Following Hurricane Katrina, they identified ways to prevent future hydraulic system failures. Their insights raised awareness that adaptations need to happen within inland communities, not just along the coast, to safeguard against future flooding.

Forming the first resilience district in New Orleans, the city and redevelopment authority prioritized a new Community Adaptation Program with $141 million from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. This program distributes funds directly to homeowners, supporting the design and construction of green infrastructure in their own backyards. This reduces stormwater from entering the surrounding urban waterways, which will continue to experience more intense storms.

Going Global

While these initiatives may not be new, they are steadily becoming more mainstream. One outcome of the UN Global Stocktake in 2023 is that all countries will be developing National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) by 2025 and are required to show significant implementation progress by 2030.

We can contribute lessons learned from our work in this space. By sharing this knowledge, we can help many countries without landscape architects or in-country technical expertise and those that are just beginning to develop their NAPs.

To support this, I am developing Supplementary Material to the UN NAP Technical Guidelines, which will be shared as a resource at COP29 and is the product of my ASLA Biodiversity and Climate Fellowship this year. During the conference, Kotchakorn Voraakhom, Intl. ASLA, and I will be workshopping these strategies with country leaders helping to develop implementation roadmaps with a goal of overcoming unique regional challenges.

More Support Needed

There is positive momentum to implement more nature-based adaptations, but we need support to change the business-as-usual mindset. The U.S. federal government has lifted up nature-based solutions. Community-based education programs like the Envision Resilience Challenge are becoming more common. And there are resources like Landscape Architecture for Sea Level Rise being published. We are making progress.

But when students from other schools still come up to me to say, “I wish I was learning more about climate change,” it means we have a ways to go. Nature-based solutions are documented to be approximately 70% more cost effective than gray infrastructure. However, most nature-based climate adaptation is not funded despite the fact that 800 million people will be affected by coastal flooding by 2050.

More studies and research to prove the effectiveness of these solutions and more built projects will get us there. But we will all need to do our part.

Pamela Conrad, ASLA, PLA, LEED AP is a licensed landscape architect, the founder of Climate Positive Design, faculty at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, and ASLA’s inaugural Biodiversity and Climate Fellow. She was the chair and lead author of ASLA’s Climate Action Plan, 2019 LAF Fellow, 2023 Harvard Loeb Fellow and currently serves as IFLA’s Climate and Biodiversity Working Group Vice-Chair, World Economic Forum’s Nature-Positive Cities Task Force Expert, Carbon Leadership Forum ECHO Steering Committee, and is an Architecture 2030 Senior Fellow.

This article was originally published on The Dirt and is shared with the author’s permission.

Leave a Reply